What's on the cloth, what's in the cloth

Where the meaning lives in cool clothes

Welcome to Blackbird Spyplane.

Our interviews with Cameron Winter and Geese, Nathan Fielder, Sarah Squirm, Adam Sandler, Brendan from Turnstile, Patrick Radden Keefe, MJ Lenderman, Maya Hawke, Bon Iver, André 3000, Sandy Liang, Matty Matheson, Laraaji, Ryota Iwai from Auralee, Tyler, The Creator, John C. Reilly, Father John Misty, Kate Berlant, Clairo, Steven Yeun, Conner O’Malley & more are here.

Our brand new Home-Goods Recon Spectacular has intel on furniture, shower curtains, dish racks, rugs, ceramics and more.

Mach 3+ city intel for traveling the entire planet is here.

Check out our monumental new list of the 50 Slappiest Shops across the Spyplane Universe.

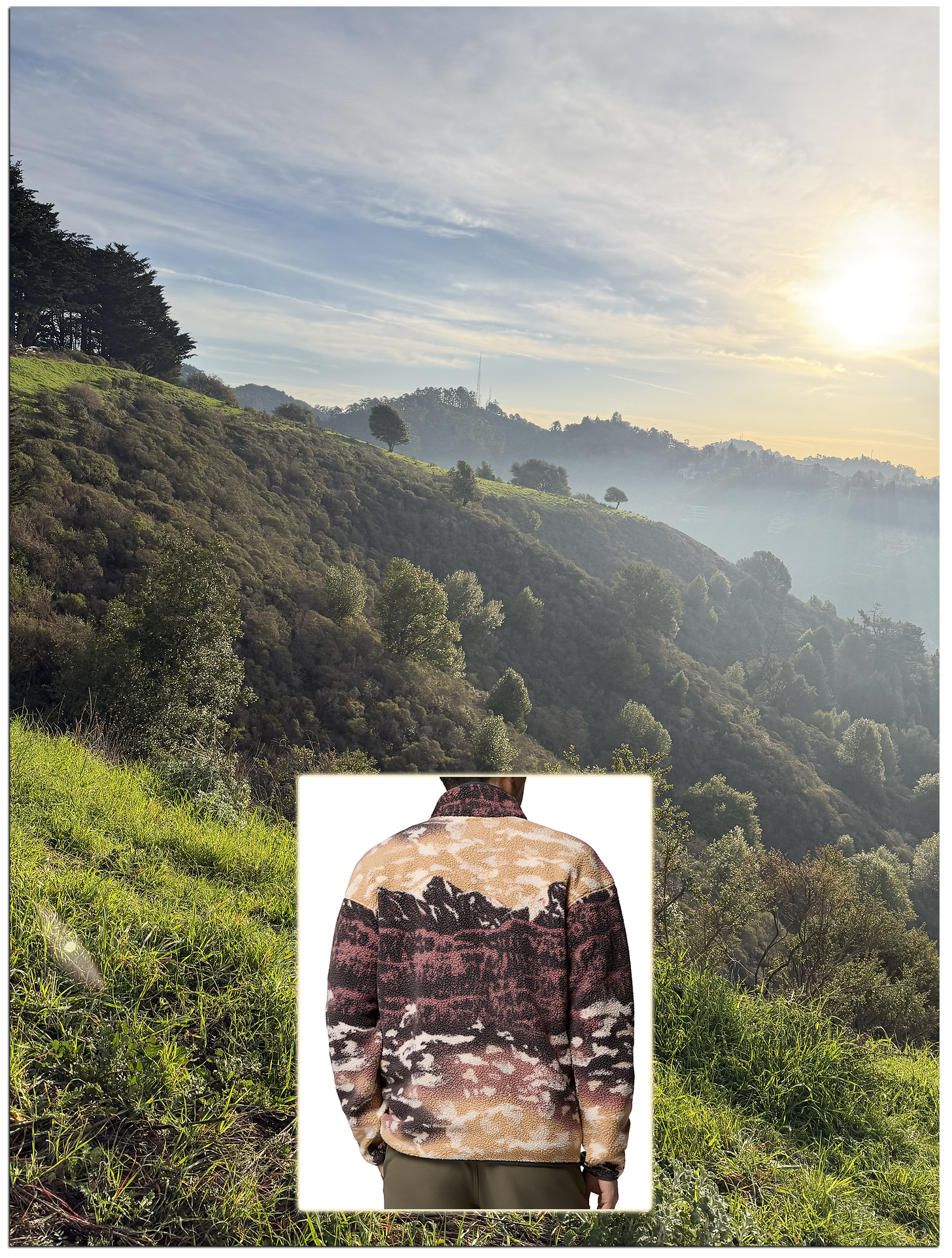

I (Jonah) was out hiking with Erin the other day when we passed a woman wearing a fleece jacket with an all-over woodland landscape print. If I had to guess, it was an REI-regs Columbia pullover that came out at some point in the past decade.

Glancing at it, I was struck by several conflicting impressions…

One, I felt a flash of pleasure at the sight of this little polyester trompe l’oeil nature scene moving amid the actual living, breathing, nature scene of the trail…

Two, it occurred to me that, a few years ago, I might have paused to ask this woman about her fleece, snap a pic, and start plotting a roundup of “vibey vintage landscape fleeces” for the sletter. Not a bad idea — very Spyplane Year One.

And yet…

Three, I felt no inclination to do any of those things, and instead simply kept it pushing up the hillside. I realized that, here in 2026, what interested me most about the landscape-print fleece was how little — or, more to the point, how fleetingly and how superficially — it interested me.

I dipped into a quick spell of craggy big-brained contemplation, and soon a profound truth dawned on me: Over the past few years, the Mach 3+ cool-clothes enthusiast has exited one era, and entered another.

The previous era was defined by a prevailing interest in what’s on the cloth.

Whereas our current era is defined by a prevailing interest in what’s in the cloth.

Landscape-print fleeces. Graphic tees. Logo hoodies. Screenprinted tote bags. Embroidered strapback caps… These are some of the most straightforward examples of clothes and accessories whose primary appeal, and primary meaning, resides on, rather than in, the cloth.

A textbook on-the-cloth garment, in other words, draws our attention away from the particulars of its fabrication and fit — away from the particulars of its own materiality — and towards its surface.

We might still register these particulars, but they are not the overriding concern: Our thoughts travel from the garment’s surface not further into the cloth, but off in the direction of the garment’s referent… toward the kitsch charms of the surreal mountain range rendered on a criminally cheap $60 plastic Columbia fleece… toward the “wealthy yet unimaginative Miuccia Prada Superfan” aura implied by the embroidered logo on a criminally expensive $2500 plastic Miu Miu fleece… toward the autobiographical details that Nick Williams of Small Talk Studio carefully and lovingly drew onto a white trucker jacket I sent him back in 2020… toward the shamanistic psychonaut vibes evoked by the Alice Coltrane illustration on an Online Ceramics tee… etc., etc.

These kinds of clothes tend to pop and proliferate on screens, because they are, very commonly, wearable symbols and signs before they’re anything else.

An upshot of this is that you could smash the Buy it Now on, say, that excellent vintage ‘90s cotton-poly Twede’s Cafe merch tee with cartoon coffee mugs slaloming down a slice of cherry pie on skis, and failing that, you could buy the vibey all-cotton repro version you saw a cool bootlegger run up on IG…

… Or? You could just screenshot it, text the .jpeg to a friend, post it to stories, and find yourself ~85% satisfied, no physical garment required.

Here at the Plane we own, love and admire all manner of garments whose primary meaning lives on the cloth, and I believe we always will. But over the past few years, our focus has shifted, burrowing deeper and deeper into the cloth. And in this we’re far from alone.

I should be clear that I’m talking more literally than poetically here. When someone invokes “the meaning that lives in cloth,” there’s obvious metaphorical potential: They might be referring to the stories, memories, emotions and fantasies that can take up residence in our garments. But, without ignoring that metaphysical dimension, I’m talking about a rising interest in clothes that draw attention toward the facts of their own materiality, to the degree they draw much attention at all.

For some examples of what I mean by in-the-cloth garments…

Think of vintage Yohji Yamamoto pants that look & move like pools of ink but are, in fact, ultra-drapey black wool gabardine, woven by a specialty mill in the ‘90s.

Think of Man-tle’s new ultrafine Supima-cotton typewriter cloth “160 Crunch” button ups, due out this spring, woven at what designers Larz Harry and Aida Kim say is a record-breakingly high density of 358 yarns per inch.

Think of the bound interior seams — invisible to onlookers, but nestled neatly against the wearer’s skin — in the imminent SS26 Evan Kinori two-pleat pants cut from an intricate grey-navy-brown linen check whose yarns were dyed at the fiber level before being spun into yarns.

Think of Cottle’s Sunset Pile fleece — which I’m wearing in today’s opening art, beside designer Toshi Watanabe — cut from a blend of yak’s wool and FoxFibre cotton, which is not dyed but, rather, grows brown naturally.

Think of the sweatshirts that Dana Lee Brown cuts from a double-faced fabric she developed with organic cotton on the exterior and Rambouillet wool inside. On a cursory glance it “just looks like any sweatshirt,” because the meaning — and the pleasure of wearing it — is not on the cloth but in the cloth.

That speaks to one major virtue of adopting a “What’s in the cloth” mindset, which is that it leads you more directly to questions of silhouette and construction, i.e. the things that make you look good in a garment as you move through corporeal space: That hoodie you love doesn’t fit you well because of the logo on the chest, it fits you well because of what’s in the cloth.

Relatedly, a “What’s in the cloth” mindset accounts for the importance of time and wear in clothes, because a beautiful or otherwise special cloth will 9 times out of 10 look better, not worse, the longer and harder you wear it — and that’s a consideration that more of us are taking into account these days when we think about clothes.

Yes, charm and meaning can absolutely accumulate in the cotton of, say, a dope old Hokusai-print mockneck — especially if you’ve owned it and been wearing it yourself since the ‘90s. But a lion’s share of that charm and meaning will always exist on the cloth, not in the cloth. Because, without the graphic, the tee might still be handsomely cut, faded, frayed and single-stitched, but it will be much less remarkable: An old Anvil-tag Tracy Chapman tee is going to thrum with more power than an old Anvil-tag blank.

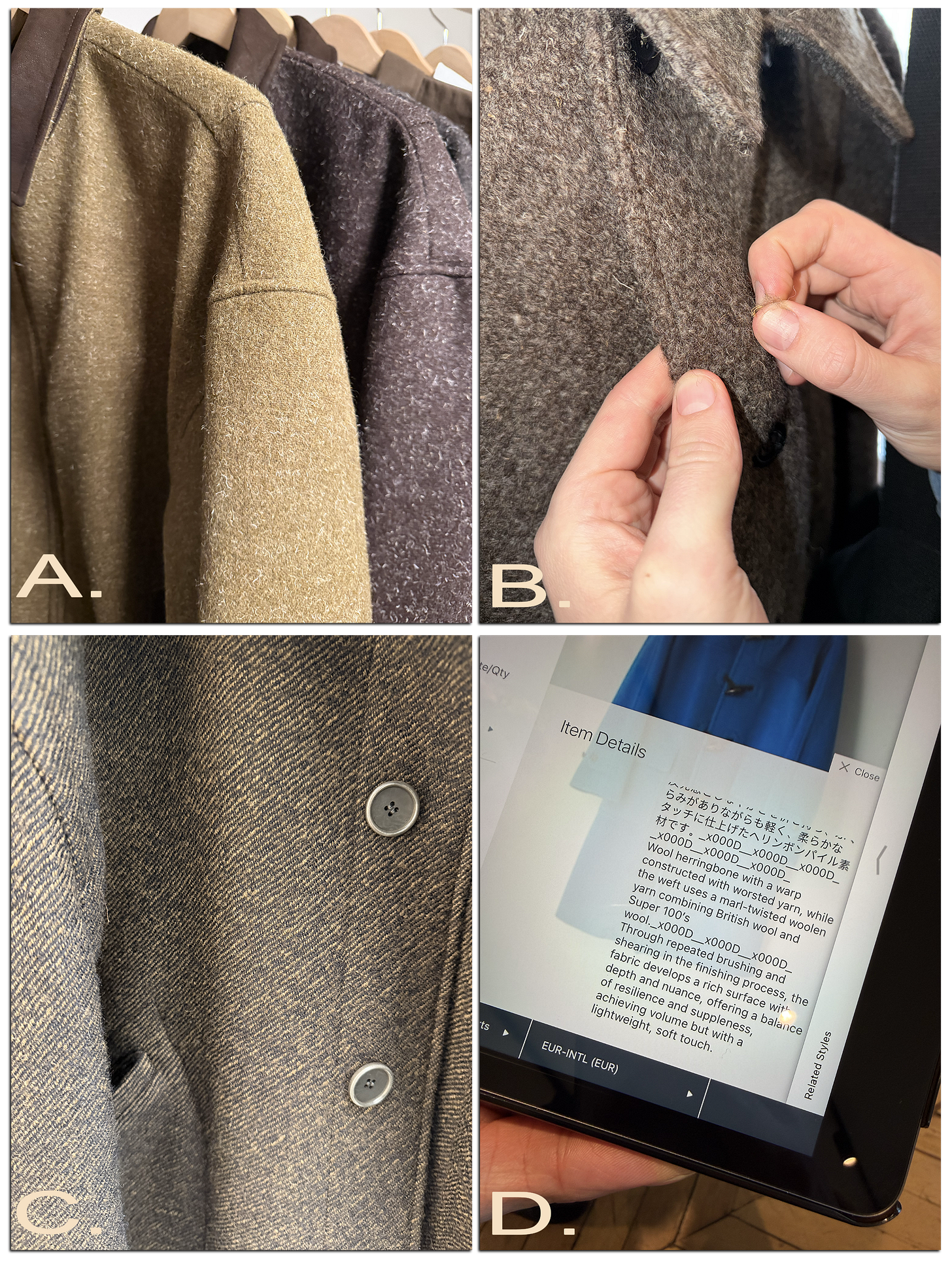

In Paris last month, I saw a ton of in-the-cloth clothes at the various FW26 showrooms. Mark Smith Clarke of NYC’s Archie showed me jackets cut with wool he’d sourced from a farm that specializes in old sheep: Their wool contains lots of dead hairs, which do not take any dye, and the result, A. below, is a snowy, frizzly effect that’s immanent to the cloth itself.

Oliver Warner of London’s Conkers plucked a piece of grass from a coat he’d made using undyed — and, it seemed, un-de-grassed — wool, B. below. “I’ve been doing this all week,” he told me. The pasture itself was embedded in the cloth, not just in a figurative sense but in a literal one, too.

At Sono, I found myself mesmerized by the wobbling, wavering lines of an “irregular double face twill woven from twisted brown and black yarns,” C. above.

At Auralee — the best-known and best-loved in-the-cloth brand of the moment — I beheld a subtly trippy brushed & sheared blue herringbone fabric. Its warp consisted of worsted yarns (all combed in the same direction, so that the fibers were tight and compact) while its weft consisted of woollen yarns (left uncombed, unaligned and fuzzy), D. above.

As you know if you read our interview with Auralee designer Ryota Iwai, he lives for this kind of s--t.

Much smaller operations are chasing a similarly geeky commitment to materials development. Middle Distance is a tiny, adventurous line from Scotland whose designer, Robert Newman, showed me a wild 3-layer rain shell he’d developed for this fall, E. above: it’s composed of nylon mesh inside, a waterproof castor-bean-oil membrane (!) in the middle, and a red waxed Irish linen on the outer face, with taped seams holding everything together.

This shell embodies what Robert called a “lo-fi, artisanal version of technical clothing” — a paradox brought to life in the cloth.

And Bill McNicol of the Cleveland line William Frederick showed me a crinkly pin-check button-up shirt, F. above, cut from linen woven in Japan’s Enshu region, apparently notorious for the violence and speed of its coastal winds. “After weaving a bolt of the linen, they hang it outside,” Bill explained, “and the wind smacks it so hard, over and over again, that it gets these permanent indentations.”

The damn wind is right there in the cloth!

Last week I wrote about the rise of “good clothes” — immanently beautiful pieces that some people are inclined to dismiss, inaccurately, as boring. Rather than using the subjective term “good clothes,” it might be more precise to say that these are clothes whose appeal and meaning lie substantially in the cloth, not on it.

Of course, on the cloth vs. in the cloth is in no way a hard-and-fast binary. A nice tie-dye sweatshirt or shibori-cloth button-up scrambles the distinction between on and in. So does a pair of ultra-slubby silk noil trousers, because a dramatic texture like that can create an eye-catching surface that pops in pictures and leads us deeper into the cloth. Ditto a beautifully made pair of, e.g., archive Dries Van Noten trousers with a hallucinatory print.

And on the flipside, a rare & intricate yet unassumingly beautiful cloth can easily become reduced to its own kind of sign of “refined discernment”— which is to say, to its own sort of fetish.

But notwithstanding these cases, the on-the-cloth / in-the-cloth distinction remains illuminating. I think it’s crucial to understanding how a growing number of Slapper Appreciators are relating to clothes lately.

Perhaps you’re one of these Slapper Appreciators yourself. Take a look at the clothes you own and love best right now — or the ones you don’t own but covet intensely. Is it what’s on them, or what’s in them, that excites you most?

P🌬️E🌬️A🌬️C🌬️E til next time,

Jonah & Erin

Enjoy our definitive Spyplane guide to the Best Japanese Clothesmakers.

Our guide to how to pack for a trip swaggily is here.

Classified-Tier Spyfriends request, share and receive Mach 3+ recommendations in our SpyTalk Chat Room.

I’ve been thinking a lot about that tweet you referenced in your recent send, in which someone said they work out not for vanity or even health, but to avoid getting lost in a world of signs.

It feels resonant with, I don’t know what to call it, a large-scale internet fatigue? Which, I think, while long simmering, has really come to an overflowing boil over the past year.

People everywhere are tired of almost exclusively inhabiting worlds of signs and symbols. We’re yearning for embodied truths.

Perhaps the same currents have pushed our collective clothing fetishes from on-the-cloth to in-the-cloth quality.

On the flip side, raw denim people have always been “in-the-cloth” appreciators, yet their little subculture was famously online.

Clearly in-the-cloth appreciation doesn’t preclude the social dimension of enjoying clothes

This was a beautiful exploration of an object’s “thingness” — have you ever read Richard Powers’ Echomaker? Has a lot of great stuff about the world of signs: “there’s nothing in this world that giving meaning makes it more” — “louder the ring, less the thing”