Are good clothes boring?

Signs and things in themselves

Before we get to today’s Plane —

In last week’s Home Goods Guide, we praised the virtues of neighborliness. Among other neighborly activities, we suggested that “you might generate a ton of noise and otherwise make yourself extremely annoying (in a based and cool way) when masked losers arrive in town and try to disappear people from your community.”

This is what Alex Pretti, like Renee Good before him, was doing in Minneapolis on Saturday when U.S. Border Patrol Agents attacked and killed him. The White House has tried to smear Pretti, but it won’t work. He was by all accounts a profoundly admirable man, motivated by love, generosity, and a sense of duty to others: an ICU nurse who loved to ride a bike through nature in his downtime.

While standing up for his neighbors, he was shot in the back by a group of small, stupid, hateful men. They deserve to stand judgment, in this life and the next, and so do the people who sent them there.

Yesterday, Spyfriend Nick Dierl put us on to a Minneapolis mutual aid group covering meals and rent for families in need, run by his childhood friend Britanny Kubricky. She’s on IG here, and you can make a donation through Venmo here.

Our friend Kirsten in Minneapolis sent us this database of other local groups, including the Immigrant Law Center of MN and the Immigrant Rapid Response Fund, doing important work on the ground.

Our interviews with Sarah Squirm, Cameron Winter and Geese, Nathan Fielder, Adam Sandler, Brendan from Turnstile, Patrick Radden Keefe, MJ Lenderman, Maya Hawke, Bon Iver, André 3000, Sandy Liang, Matty Matheson, Laraaji, Ryota Iwai from Auralee, Tyler, The Creator, John C. Reilly, Father John Misty, Kate Berlant, Clairo, Steven Yeun, Conner O’Malley & more are here.

Maybe it was all the grass we touched. Maybe it was all the bread we baked. Maybe it was the widespread collapse of belief in institutions, and the countervailing swell of interest in older forms of communitarian connection. But since the pandemic, the most exciting story in The Cool Clothes Universe has been the rise of small independent makers united by their shared interest in

craft,

innovative, elegant uses of natural fabrics,

unrestrictive silhouettes,

muted color palettes,

an aversion to trends,

and a generally pared-down aesthetic that speaks with eloquence when you see it in person, even if it might feel opaque and inert when you encounter it on a screen.

As a catch-all term for this approach, “Slow Clothes” isn’t perfect, but it gets the point across.

“Slow Clothes” includes single-maker lines like Toronto’s Henry’s, Kyoto’s Akari Tachibana, and Paris’s Oliver Church. It includes slightly larger labels like Bowen Island’s Dana Lee Brown, San Francisco’s Evan Kinori, Vancouver’s James Coward and, out of London, Conkers and Sono — labels that operate under a tight set of self-imposed aesthetic, ethical and ecological constraints designed to protect and preserve the meaningfulness of the clothing they make and how they make it.

The term includes small- to medium-sized materials-development wizards like Perth’s Man-tle and Tokyo’s Auralee. It includes earnest, off-on-their own trip artisan lines like Pennsylvania’s Tender Co., Okayama’s Cottle, NYC’s Lauren Manoogian, and Antwerp’s Unkruid and Jan-Jan Van Essche — and it includes winking postmodernists like Amsterdam’s Camiel Fortgens and Copenhagen’s Mfpen.

It includes an armada of tasteful and increasingly buzzy Japanese labels, like Comoli, Stein, and Niceness, and A. Presse. And it includes paragons of swaggy consistency, like Margaret Howell and Lemaire, the latter of whom have gotten about as big as a Slow Clothes brand can get before the words lose meaning.

A huge part of these lines’ appeal derives not just from the fact that their best clothes are very pleasant to look at, to touch, and to wear, but also from the refreshing contrast they present to bloated, out-of-touch, corporate-owned fashion houses (on high); hype-heavy, artificial-scarcity-dependent streetwear brands (in the middle); and the world-killing Garbage Demons of fast fashion (down below).

This s--t all feels like depressing junk, top to bottom, to more and more of us. Churn is its organizing principle. Big money at its most noxious and unsexy has captured the “high fashion” space and is steadily choking away its remaining dregs of glamor, which was always largely illusory anyway: Uncool freaks like Jeff Bezos and Lauren Sanchez sponsor the Met Gala and hang out with Jonathan Anderson in Paris; conglomerates like LVMH put obscene profit margins above all other concerns, including not just labor conditions (what else is new) but the quality of the goods they sell, too — see the $2800 Dior handbags that cost LVMH $57 each to produce, in what Italian authorities have described as sweatshop-like factories.

No surprise, then, that luxury brands are losing their luster, and that the Luxury Customer is no longer some aspirational figure, but rather a pitiably hoodwinked soul and/or laughably delusional chump who buys clothes at the airport. Luxury revenue is on the wane. The bottom has already fallen out of the streetwear market. And so retailers who used to print money selling logo handbags and doing endless sneaker drops now find themselves forced to pivot and “mature” their offerings accordingly — in other words, to embrace Slow Clothes.

In the fashion media, a parallel pivot is underway. Trust has cratered when it comes to established publications (not to mention a constellation of in-the-pocket influencers), which still have to pretend that the deep-pocketed brands that advertise with them are doing important & interesting work, and that the celebrities these brands dress for events and sign to endorsement deals (and in some cases appoint to creative director roles) are putting that s--t on.

The result is a hemorrhage of editorial credibility. Cool-clothes enthusiasts are smart enough to see through this. And so you have a beautiful & blessed “first mover” newsletter like Blackbird Spyplane gaining in influence and finding an audience of millions over the past 5 years while running zero ads and forswearing affiliate links.

You have a place like Highsnobiety overhauling its mandate last year to focus on “Good Clothes,” as the magazine’s new Editor-in-Chief, Spyfriend Noah Johnson, phrases it. You have our buddies at Throwing Fits going justifiably cuckoo on the podcast for lines like Auralee (which topped their 2025 listener rankings of the best brands out, an outcome that would have been unthinkable a year ago) and, just yesterday, bringing Keith Henry, of Henry’s, on to the pod. And you have an array of little-mic IG video personalities and Substack link dumpers following suit and rhapsodizing about small artisan lines, too — following the money, the energy and, hopefully somewhere in the mix, their own interests.

Add it all up, and Slow Clothes are objectively more popular than at any previous point since the pre-industrial era, back when all clothes were slow.

That’s a good thing, isn’t it?

Well, it depends on who’s asking. This past fall, Business of Fashion diagnosed a “sameness epidemic” in menswear, noting, in effect, that there is a thin line between tasteful and bland, between subtle and indistinct, between muted and boring.

BoF is fashion’s leading trade publication, and they pointed to the most obvious market obstacle the Slow Clothes trend faces, which turns out to be the same market obstacle any trend faces once it reaches critical mass: customer fatigue.

That critical mass, if we haven’t gotten there yet, seems to be on the near horizon. In December, an IG style-tutorial dude whose taste is very different from ours expressed his bafflement at the growing cachet among “fashion bros,” as he called them, of “Auralee, Comoli and that kind of broader minimalist ecosystem.” He praised “the quality and construction” of these brands, but wanted more oomph in the designs. He failed to see “the appeal of slightly oversized taupe shirts and brown pants” — of clothes that seemed, to him, “built to disappear.”

He concluded that that the growing interest in these clothes must be about something other than the clothes: “If something only means something because it’s expensive and hard to source, the actual meaning isn’t in the clothes.”

OK — good clothes aren’t for him. But he raises some interesting questions. Are good clothes objectively boring? Are Slow Clothes Appreciators just status-obsessed reactionaries intent on shelling out exorbitant sums of money to 1) signal their wealth and discernment and 2) look like a bowl of oatmeal?

There is, of course, something to that. We’ve seen a version play out among women’s clothing lines like The Row — a once-great line whose phalanx of uninspired, money-grab imitators has, by this point, come to include The Row itself, which used to have a smell, and now has none.

On the menswear side, meanwhile, color and pattern absolutely do frighten a lot of guys. Both are in something of a downswing, even if brights are on the comeback trail. The bold graphics that dominated a few years ago have come to feel torched and undignified. It’s never hard to see the allure of a certain risk-averse asceticism among the fellas when it comes to clothes, and the case could be made that this asceticism is ascendant right now.

But I don’t think that’s really what’s driving the anxiety here. What I see, instead, is people grappling with a contradiction that’s been latent in Slow Clothes all along, but which is only now starting to come into full flower.

The guiding tenets of an archetypal Slow Clothes designer are, after all, their aversion to trend and churn, and the aesthetic and material safeguards they try to create against disposability. In other words, they make clothes that reward wear over time, cut from materials that look better the more you cook them, and which, no matter how “elevated” the fabrics might be, speak in a fundamentally utilitarian (and therefore durable) workwear- and militaria-derived idiom, rather than a more whimsical (and therefore perishable) design language.

And the contradiction here, of course, is that these putatively anti-fashion labels, while remaining small, have now become inarguably fashionable: The “anti-trend” ethos is, for the time being, extremely on trend.

Any trend that reaches a certain threshold of popularity will, by its nature, generate all kinds of unsavory behaviors, and attract all kinds of unsavory characters. Among these are, on the supply side, carpetbagging shops and brands who see a chance to cash in with a little artisanal astroturfing — Zara creating fake “small artisan stores” and collaborating with small independent brands; H&M paying IG style dudes to tell you that something called “H&M Atelier” is cool in between posts about how Comoli is cool.

On the consumer end, a horde of newcomers are rushing into what previously felt like a gentle, sparsely populated rare-bird sanctuary. If you are looking at this horde from inside the sanctuary, you might be tempted to get territorial and defensive, the way the members of any subculture are prone to do.

If you are looking at it from outside the sanctuary, what seems like bewildering, lemming-like hype might perplex and annoy you, and — much like the seeming arrivistes you disdain — you might be prone to ignore what is actually great about the clothes.

We’ve written here at the Plane about how there is, in the final analysis, no escaping trends, and how there’s no such thing as “timeless style.” We’ve written about how “wack” people can ruin the things you love and, not unrelatedly, how clothes are irreducibly social, which makes “Stop caring what other people think” bad advice if you care about clothes.

These are all arguments that treat clothes, fundamentally, as a symbolic language.

But there’s another element at play when it comes to Slow Clothes specifically:

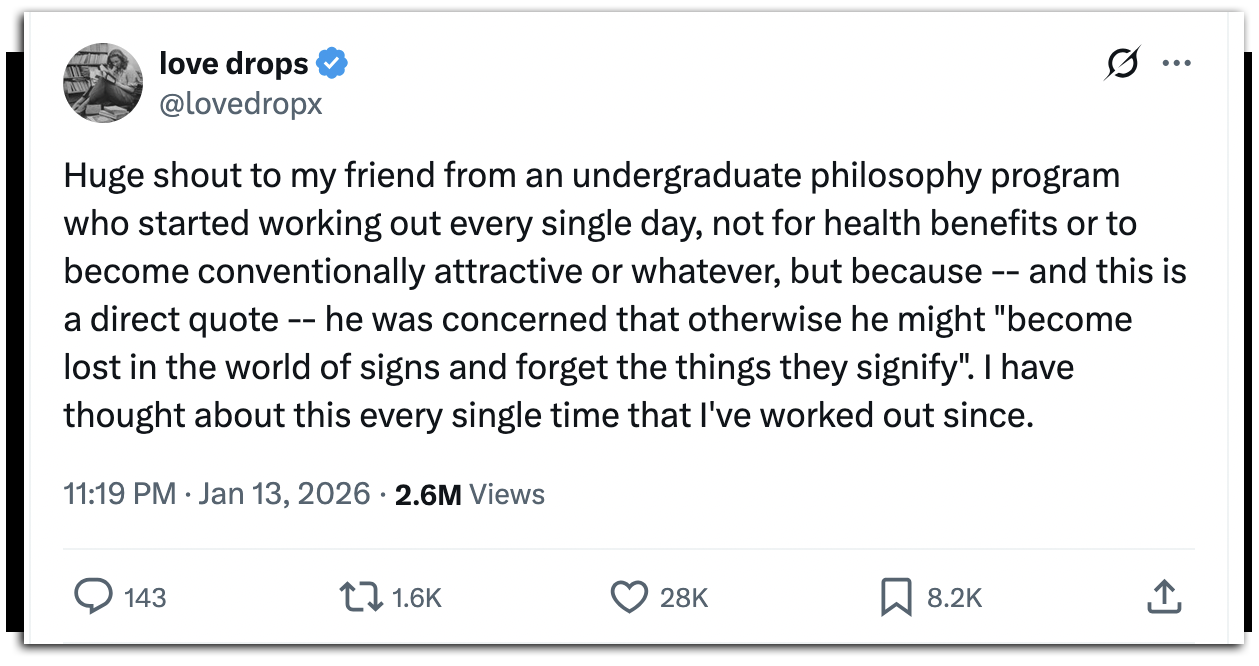

Circa 2026, we have grown unprecedentedly tired and mistrustful of the World of Symbols and Signs. We want to engage, instead, with the World of Things in Themselves.

And a defining promise of Slow Clothes — with their emphasis on natural dyes and natural fibers, rather than synthetics, with their insistence on their own materiality, which is to say, on their own madeness — is that they are not merely signs, but Things in Themselves.

Contra the POV of a dude who wants to buy these clothes because he gathers that they are IYKYK status symbols — and contra the POV of a dude who disdains these clothes because he gathers that they are IYKYK status symbols — their most potent meaning does in fact reside in their warp and in their weft, in the interior seams that no one else knows are there but you, in their palpable connection to the earth that grew them and to the hands that made them.

Can this sense of connection become its own set of fetishes? Does it threaten to collapse into its own earth-toned morass of marketing buzzwords and signs? Of course — in the current arrangement of things, that’s all but inevitable.

But are we fooling ourselves if we think it might be an off-ramp, too?

Peace til next time,

— J & E

The Blackbird Spyplane Profound Essay Archive is here.

Check out our monumental new list of the 50 Slappiest Shops across the Spyplane Universe.

Classified-Tier Spyfriends request, share and receive Mach 3+ recommendations in our SpyTalk Chat Room.

Does vintage have more Thingness (even when it also may act as a signifier)? Does clothes that has been lived in, regardless of its origins, have more Thingness? Does an Uniqlo "fast fashion" t-shirt that you've worn hundreds of times become in some way Slow through its being worn? Does a synthetic gorpcore piece become more less of a signifier and more Thingy by being worn to do genuinely gorpy activities in The Great Outdoors?

Truly fascinating topic and concepts. Thank you!

I want to argue against whimsical = perishable. Whimsy in a clothing context to me here is just a challenge. It is certainly easier to achieve with all available materials, colors, and processes. I want to believe that it is still possible to be sustainable and whimsical though.

Begs the questions, what is whimsy and what is sustainability?