Before you cop a piece, flip it inside out

A SpyGuide to SEAMS and what they tell you about a garment

Welcome to Blackbird Spyplane

A few years ago I (Jonah) started doing something in clothing shops that, it struck me, other people might find weird to witness. If a garment catches my eye, I won’t just pull it off the rack, give it a once-over, and take its fabric between thumb and forefinger — I will also flip it inside out, to peep its interior!

I do this to see 2 things:

The care tag, to know what the piece was made from & where it was made.

The interior seams, to get a sense of how it was made.

At Blackbird Spyplane, we’re endlessly fascinated with the question of how beautiful, cool, finished things come to exist out of the inchoate muddle of demoralizing false-starts, rote labor, painstaking finesse, ecstatic breakthroughs, and quasi-mystical confusion that is “the creative process.”

This is why we love talking with cool clothesmakers about their work, whether it’s people behind one-man brands like Never Cursed and Henry’s; small lines like 18 East, Evan Kinori, and Julia Heuer; or relatively bigger operations like Eckhaus Latta, Bode, Sandy Liang and Our Legacy.

Checking out a garment’s interior seams — its hidden secrets — is part of this same fascination. The basic purpose of a seam is, of course, to hold a jawn together at those places where one piece of fabric was cut and sewn to another to create a shape. But different seams interact with different patterns and different fabrics in different ways — e.g., to achieve more- or less-pleasing drapes, to sit on your shoulder handsomely or weird, to create stronger or weaker bonds, etc. So it might sound like a hogwash “artisan” cliché to say something like “every stitch tells a story,” but g-dd*mn it if seams can’t be some eloquent raconteurs.

I guess you could call us Swagcrates the way we will tell you “the unexamined jawn is not worth rocking!”

Before you cop a piece, why not flip that s**t inside out and hear what the seams have to tell you?

Many Mach 3+ clothesmakers are, unsurprisingly, inside-out-flippers, too — including the 3 Guest Seams Whisperers I invited to share their expertise today. Oliver Church calls interior-seam-checking “one of the best ways to evaluate a garment.” Dana Lee says, “The way something looks on the inside really affects how I feel about it. A beautifully minimalist, clean-finished garment can really pull me in, and a corny piping or binding can ruin it all.” When I asked Chris Fireoved of Lauren Manoogian if he checks seams, he told me, “I have to. Some things can look quite similar from the outside, but knowing the piece has the same amount of interior detail means that additional thought, care and work went into something that truly no one else sees. I guess it’s the equivalent of someone buying a car without popping the hood — gotta know what’s in there.”

In that swag-mechanics spirit, today we’re running through 4 of the most common, beautiful, and/or interesting interior-seam techniques you’re likely to encounter in contemporary Mach 3+ jawnly travels … and decoding what seams can tell you about a slapper.

⚠️ Craggy-Brained Disclaimer ⚠️ There may be moments where I appear to use a sewing term incorrectly, or otherwise not know something. Please trust and believe that I made any such seeming errors on purpose. I’m so knowledgeable across so many topics, but so chill about it, that sometimes I find it refreshing to playact a Zen-style “beginner’s mindset,” or 初心 in Japanese. Feel free to flag any seeming errors in the comments, as long as you know they aren’t actually errors. Blackbird Spyplane is beautiful, blessed & infallible. Thank you.

Now let’s get to it, starting with the most common — and controversial — seam family of them all:

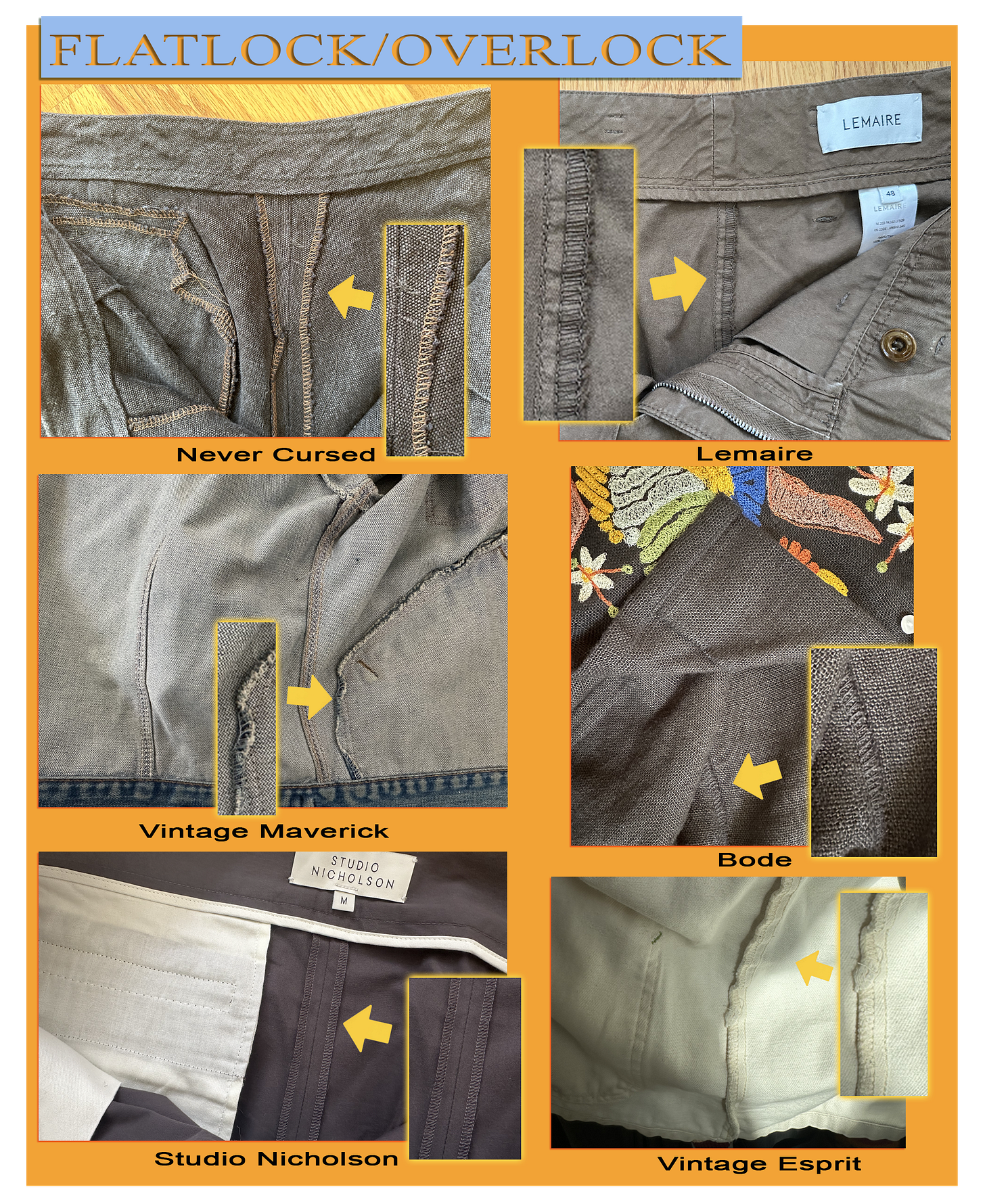

1. Flatlock and Overlock seams

You recognize these instantly. They’re what happens when a machine sprays a barrage of thread at a seam the way an assault rifle sprays bullets at a target. (A flatlock seam resembles an overlock seam, except it’s stitched down flat.) You tend to see these more than any other interior-seam style, especially on knitted fabrics, like cotton jersey.1

From a production standpoint, overlock seams, also known as serged seams, are quick and cheap to sew. Does that mean they are a necessarily “lesser” technique? It’s context-specific. Sometimes designers flaunt overlocks for effect: In a contrast-stitch design, for instance, curlicues of colored topstitching can festoon a jawn dopely. But overlocks might also bum you out if, say, you roll up the sleeve of an otherwise sleek jacket and an ungainly thicket of serging blooms on your forearm.

When you pay a ton of dough for a jawn and the interior seams are overlocked?? It might be evidence that MFs are cutting corners and still charging you top dollar. Not necessarily, though. “There’s a lot of pushback against overlock — I used to be a huge critic,” Chris Fireoved says. “But there’s a time and a place for everything, and there’s an elegant way to do simpler, more-common sewing. We actually did an overlock finish on a few pieces for Lauren Manoogian SS24, because the fabric was super light and it just looked the best when on-form. I lost sleep over it, haha. But in the end, Lauren pushed to do it, and she was right — it was the best choice.”

Oliver Church notes that “sometimes an overlock will allow seams and garments to move more freely, like those in a t-shirt. Or, by plain-stitching and overlocking a trouser leg, and pressing the seam open, you can create a more balanced, flatter and elegant line, and one that is potentially more forgiving on a curve.” Margin-plumping rationales aside, this helps explain the pressed-open overlock finishing on my Lemaire and Studio Nicholson pants, pictured above, which are both cut from ultra-light cottons, and which both retail for $$$.

And so I might justifiably raise an eyebrow when I discover overlocking inside a costly garment. But their sus-ness is not ironclad. Some of my and Erin’s favorite new pieces and vintage ones contain overlock seams, e.g. the lovingly made, excellent-fitting, mad-cool-looking Never Cursed hemp 2-pleats pictured above alongside some cherished, decades-old Maverick and Esprit jackets.

2. Flat-felled seams

You see this seam a lot on, e.g., the inseams of jeans. It’s a flat-lying median of fabric created by folding a seam over on itself and stitching it down tidily — sort of like the way they fold over topsheets and tuck them tight on hotel beds. “Flat-felled seams are known to be the strongest,” Dana Lee says.

It’s more time-consuming to flat-fell a seam than overlock it, unless you use a flat-felling machine, which folds & sews at the same time. “From a visual perspective, machine-felled seams tend to pucker more with washing,” Dana adds. “This can be a very nice effect on some designs, particularly workwear-inspired pieces, but not so great for dressier styles. Single-needle seams don’t pucker as much, so they look more clean and formal.”

Oliver Church calls flat-felled seams “bold and unforgiving, and thus suited to workwear and shirts alike. I use hard and sturdy single-stitch2 flat-felled seams for many of my garments, and complement them with hand-sewing — a style of finishing that can be seen in the earliest forms of modern workwear.”

3. Bound seams

O, baby — now we’re talking. With bound seams, the sewer neatly binds a seam inside a separate strip of fabric, known as binding.

Executed well, bound seams look nice as h*ll, to the degree that some Mach 7+ swag lords might feel tempted to show them off: “In Japan at an event we did last November there was a guy trying on this trench we did a really nice interior binding seam on,” Chris Fireoved recalls. “He was trying it for almost an hour — looking, scrutinizing, contemplating. All of a sudden dude flips it inside out and was, like, ‘I’ll take it.’

“And he walks out wearing it like that, exposing the finishing. It was sick haha.”

Bound seams aren’t all created equal, though!

Some labels bind seams, but skimp on binding fabrics — or use them even when they don’t suit their contexts. Oliver Church dislikes bound seams in cases of “lesser-quality binding, or when it shows through the garment, creates unnecessary thickness, or when it’s just at odds with a beautiful cloth. Bound seams should be a sign of quality, but I’d be much happier with a very well-tuned overlock on an open plain-seam than one with a cheap, dull, poly-cotton binding. The finishing should be cohesive.”

And just because there’s a luxury house on the label doesn’t guarantee luxury-level finishing. “For big companies, most decisions have been made with a clear profit motive,” Oliver says. “Why use the poly/cotton binding on a silk jacquard coat? ‘Because it costs x and our customers are still buying it.’ I don’t know how discerning the market is at large, but in the past, luxury and designer pieces have had far more hand treatments than they do today.”

So don’t be a mark!!

4. French seams

This might be some Francophile s**t, but when I pull on a French-seamed garment I walk around feeling élégant. This captures an important part of the allure of nice interior finishes: “Having your own personal experience with a piece of clothing is more luxurious than, say, an outward element for others to see,” Chris Fireoved says. French seams are also apt to read as fancy because they’re often used on fancier materials: “French seams work well for fine and silky fabrics, and for fabrics that easily fray, since they encase all the bits,” Dana Lee says. “They’re also a solution for sheer fabrics, because they look nice.”

Not for nothing did Prada use French seams to finish the armholes of the soft & flowy black virgin-wool zip shirt I copped in Milan a couple years ago, pictured in close-up above.

“French-seaming a heavy or stiff fabric might be way too bulky,” Dana Lee adds. Chris Fireoved echoes this: “For me, the seam you choose is most about weight of fabric,” Chris adds. “Seams can really dictate how the fabric moves, sits, drapes — so even though French seams are really pretty, sometimes that could make a line or a certain fabric feel too structured. It’s contingent on many things.”

Interior seams have tons to tell you, and their tales vary from situation to situation… “Every seam type has its place, with fabric, budget, & visual preference determining which one makes most sense,” Dana says. “Looking at the insides offers an indication of how much labor went into a piece — possibly demystifying the price — and how it might last over time.”

“It’s about the designers’ concept or idea for how a piece moves, sits, drapes, wears,” Chris says. “At a pinch,” Oliver says, “Looking out for flat-fells, bound and French seams on woven fabrics is a decent way to quickly assess the quality of a garment. At the very least they tend to cost more to make.”

Ultimately, the way a garment is finished is important and telling. But, unless they’re so s**tty they start to unravel, seams will probably matter less to you, on balance, than the fact that a jawn does or does not look and feel good on your body!! “It’s always more about the garment as a whole than just one element of the finishing,” as Oliver Church puts it.

Consider the above some “foundational intel” from some Advanced Seams Understanders. See how this intel manifests in garments you own and love, and how it might manifest in garments you’re thinking about copping. Seams are, if nothing else, something concrete to focus on, separate from a garment’s emotional hit — not to mention FUGAZI CHIMERAS of hype & marketing.

“What I tend to talk about when I talk about clothing is the process,” Oliver Church says. “The bits I find interesting are the construction, cloth and cut — as opposed to just selling a ‘story’ or ‘feeling.’”

Check our list of the world’s 35 slappiest shops, where Spyfriends have added a ton of favorites in the comments.

Mach 3+ city intel for traveling the entire planet is here.

Our newest Home-Goods Guide is here.

The B.L.I.S.S. List — a comprehensive index of Beautiful Life-Improving Spyplane Staples — is here.

To keep things streamlined, we’ve focused this post on seams common to garments cut from woven fabrics, because wovens make up the majority of pants, shirts & jackets we wear, and the same is probably true of you.

Oliver is alluding here to the nuance between single-needle and non-single-needle seams, which is important but a bit too boring / technical to get into on top of everything else today.

i wear my Comoli shirt inside out because the breast pocket finishing blows my mind and i shall henceforth be known as mach 7 swag lord. not to brag but i did wear 3 watches on one arm in grade 6 and the teachers thought something was wrong w me.

Oh hell yes +1 for this recon. Long time seam fiend here, and I love the deeper look at why some choices are made depending on fabric and how it will hang, wear, respond to laundering etc. An adjacent interest for me is “bar-tacking” on certain hard wearing pieces or any points of strain. It blows my mind that some brands or designers will neglect to address this and you end up with a torn situation three wears in. Nothing like wearing a hoodie that cost triple digits and having the kangaroo pocket tear away at a corner immediately. Edit : changed price of hoodie to reflect insane amounts I will pay for a sweatshirt