The internet is rigged against great stores

Can they thrive by staying offline? A Blockbuster Spyplane Investigation

Our brand-new 2024 G.I.F.T.S. List, bursting with slappers for the mind, body and home, is here.

Mach 3+ city intel for traveling the entire planet is here.

Our interviews with Adam Sandler, Kim Gordon, André 3000, Nathan Fielder, 100 gecs, Danielle Haim, Mac DeMarco, Jerry Seinfeld, Matty Matheson, Seth Rogen, Sandy Liang, Tyler, The Creator, Maya Hawke, King Krule, Steven Yeun, John C. Reilly, Conner O’Malley, Clairo, Father John Misty and more are here.

One of the many compelling contradictions of Blackbird Spyplane is that even though we’re an internet miracle, we think buying clothes in person is much tighter than buying them online. Notwithstanding the miraculous convenience of scoring a far-flung banger via worldwide e-comm channels, we believe the ideal way to buy a garment — and the surest way to feel happy about it— is to run your palm across the fabric, hold it up to the light, flip it inside out to check the interior seams, and then observe how its molecules link & build with your physical form as you put it on and move together through space and time.

This is why Erin and I (Jonah) love to celebrate great small shops alongside great small lines — they’re mutually beneficial parts of the same Endangered Slapper Ecosystem. And it’s why we have a particular fascination with the extremely rare, borderline-inconceivable-circa-2025 phenomenon of great stores that refuse to sell clothes on the internet at all.

We’re thinking of shops like the highly respected Les Étoffes in Montreal (est. 2008), which might have been the first across North America to stock Lemaire; Elise in Leamington Spa, England (est. 2002), who carry Oliver Church, Casey Casey, Bergfabel and Kaval; Tusk in Chicago (est. 2013), who stock a mix of clothes and home goods; New High Mart in L.A. (est. 2007), ditto; or the legendary MAC a.k.a. Modern Appealing Clothing in San Francisco (est. 1980!), who are longtime stockists of Comme des Garçons, Sofie d’Hoore, and Dries van Noten, among other Mach 3+ lines.

I tend to assume that shops like this grandfathered themselves in, putting down roots during earlier, more hospitable eras for independent, brick & mortar retail; cultivating faithful local clienteles; avoiding overextending themselves; maybe signing below-market leases before real estate prices went nutty and the ship sailed for good. But over the past few months I’ve been intrigued to see a few Mach 3+ clothing-retail veterans opening cool new shops without any e-comm. Are these people handicapping themselves? Can they really give the Internet a miss and survive?

Or maybe those are the wrong questions. What if these shops are in fact sidestepping the increasingly brutal math of the E-comm Race to the Bottom, and trying to win a longer game instead?

If so, the implications would be profound. I decided to go Spyplane Deep-Reportage Mode and get some answers.

I. The best new clothing store in the world has no web shop

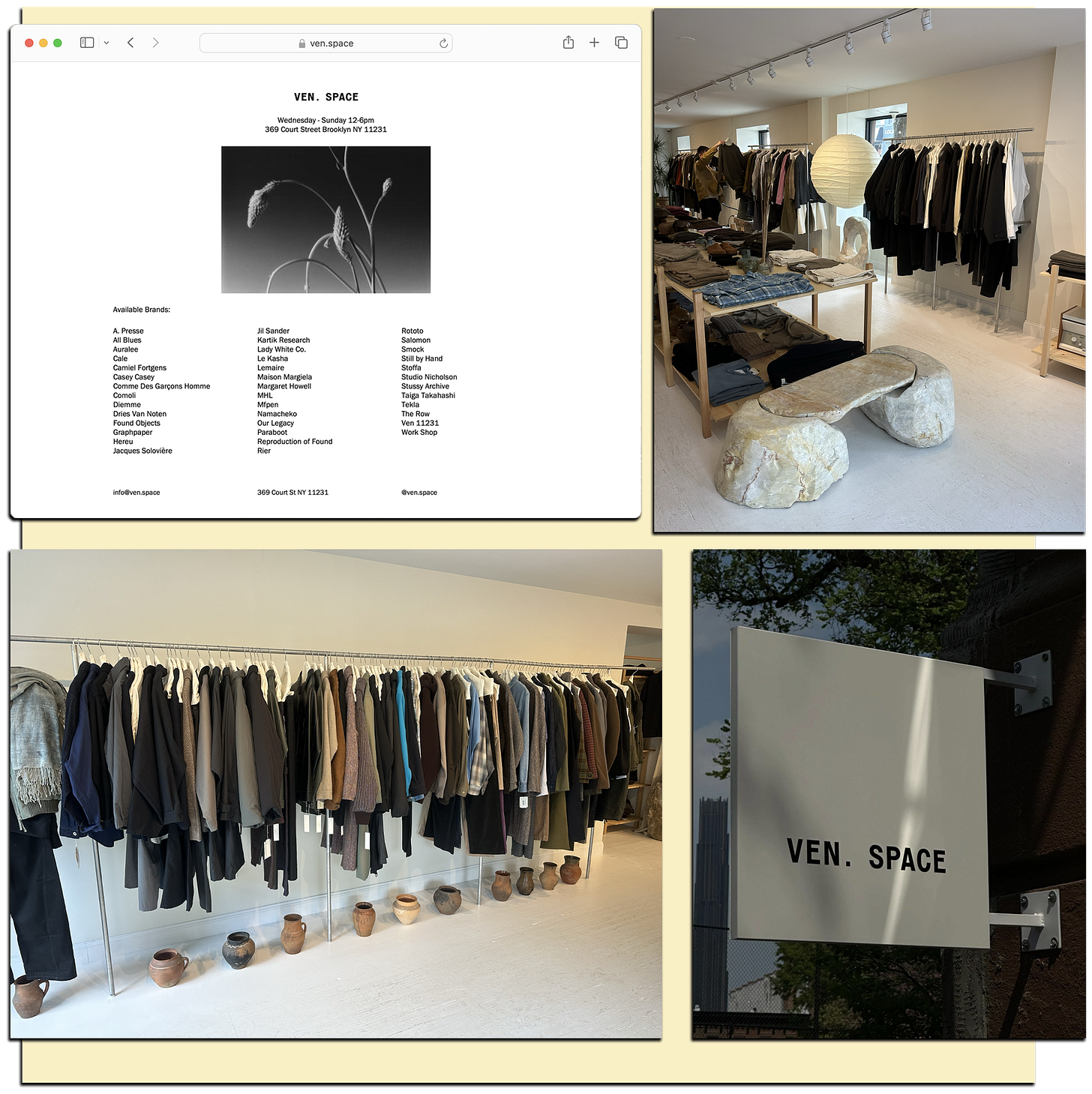

My explorations began at the best new men’s clothing store in the world. Its website consists of a single white page. Up top is the shop’s name — Ven. Space — along with its hours and street address in Brooklyn. There’s a black & white photograph of curving grasses and, beneath this, the 40 labels that Ven carries: an illustrious rundown so crowded with heaters that, when I first saw the site a couple months before Ven opened, I literally did not believe it. Below that litany is an email address, an Instagram handle, and the street address once again, as if to underscore the central point: “Come on by.”

When I popped into Ven. Space one Thursday afternoon in early October, I was one of several people browsing the racks. The shop had been open just a few weeks, and Ven’s owner, a thoughtful, handsome & stylish king named Chris Green, told me business had been brisk. This was reassuring to him, because he has no plans to launch a Ven webshop, and harbors intense hopes he’ll never have to. If you want to see which pieces he’s picked up from Auralee, A. Presse, Comoli, Graphpaper, Hereu, Lemaire, Lady White, Margiela, Margaret Howell, Reproduction of Found, Rier, Taiga Takahashi, or any of the 28 other lines he stocks, you might get a glimpse on the shop’s IG, but the only surefire way is to swing through.

“I’m not growth hungry,” Green said the other day. “I just wanna have a good, stable shop.” Before he opened, he explained, “I did my homework” on how to make Ven viable “at a very high level” with zero dependence on e-comm revenue. “It was, ‘What’s my projected sales, where’s my comfort zone, where’s the tipping point, where can I have slow weeks, or slow months, and still pay for rent, the inventory I want, and wages for my staff?’”

Part of Green’s aversion to e-commerce is philosophical. “Look at retail in Japan — a lot of the best stores don’t have particularly high-functioning e-comm, if they have e-comm at all,” he said. “Their sites are more about being informative about the clothes, less about selling them. The emphasis is on people coming in and seeing things in person. I feel the same way.”

In that spirit, Green had custom cloth hanger-covers fabricated for Ven that he Pantone-matched to the shop’s ecru walls and designed to hide garments’ labels. “I want people to touch the fabrics, look at the shapes, talk with the staff, say, ‘This is special’ — and then see who made it and the price,” he explained. He preps his three sales associates on the clothes much the way a chef briefs his waitstaff on the menu. “They have to try on every single piece in the store,” Green said. “See where it’s made, what it’s made from, learn why it costs what it costs, the fit, the stitching, the trims, so they can talk about it all.” This way, “we’re hopefully building an environment where the customer is getting a service, and after they’ve tried something on and talked to us and we’ve helped them, they’re not gonna suddenly get price conscious and try to go buy it online for less.”

The other part of Green’s aversion to e-commerce is, perhaps counterintuitively, financial: Selling clothes online is a putative revenue stream, he explained, that can become a revenue drain, throwing money away with one hand while bringing it in with the other. He described e-commerce circa ~2025 as a rigged game, where shoppers intent above all on hunting down a garment at the lowest possible price treat the internet like a giant, undifferentiated sales floor they can sort by price, Low to High. “If you’re small, unless you’re offering a truly unique product, it’s hard to win in that landscape,” against bigger online players with “the money and the scale to do things like discount their stock early and pay for SEO,” Green said. “Google is a massive offender of that. You’re paying to show up high in search, and the more you pay, the more relevant you become. So for a small brick-and-mortar, just paying for the SEO alone is insane.

“On top of that,” he continued, “you have to pay for a certain level of online customer service.” You’ve got to produce beautiful photographs of the clothes, measure them, write descriptions, field email inquiries about their particulars. And then “the expectation has become free shipping and free returns,” he said, “and that’s a really hard burden for a small boutique to take on. Ssense and Amazon can do it because of their scale — but they’ve created this insane expectation that everyone else should do it, too.”

To be sure, if you have the talent and resources necessary to create a top-notch webshop — like, say, the Spyfriends at Vancouver’s Neighbour and Portland’s Stand Up Comedy, to name just two — you can turn it into a world-class extension of your world-class store, achieving a result that’s greater than the sum of its parts. The people behind these shops are masterful not only at identifying and buying cool clothes but also styling and shooting them, and their sites showcase this wonderfully. But that takes time, manpower and money, and it’s an open question of whether even a fantastic site can claw enough sales back from the Vibeless Multibrand Ecomm Bulldozers to justify the outlay.

And yes, we gotta acknowledge how far-flung slapper-copping embodies the fundamental promise of the internet: spreading information far & wide, connecting geographically disparate people with likeminded interests. If you’re a small maker, e-comm is a great way to sell your home-made jeans or ceramics to people all over the world. From a copper’s perspective, it’s obviously wonderful to be able to discover & purchase pieces from distant shops, not to mention subscribe to life-improving style & culture newsletters:

But we’ve all seen countless examples by this point of how the early dream of Internet Connectedness has been co-opted and twisted into a downward spiral by huge companies who want to re-shape the world according to their profiteering, enshittifying prerogatives.

And Chris Green knows the curves of this downward spiral firsthand as it relates to clothes. Before starting Ven, he was a buyer for Need Supply and Totokaelo, two once-beloved, once-independent brick & mortar shops that were acquired by the same corporate parent and shuttered in 2020 after overly aggressive expansion.

Green told me that those shops suffered from a host of problems, including — yes — shipping costs: “I saw how unruly the shipping and returns situation was. It really damaged the gross margin of the business, ate into the profitability. And we never reached the scale effect where, OK, you lose a bunch of money over here, but you sell so much other stuff it covers that cost.”

Instead, he said, “you find yourself in a situation where every new sale eats into the bottom line. And that makes it hard to be successful.”

II. “I would rather take the money for a targeted ad on IG and sponsor a Little League team”

I (Jonah) grew up in Brooklyn, not far from Ven — my dentist’s office was just a few blocks from Chris’s storefront on Court St., a tree-lined strip with cheese shops, old Italian bakeries, produce stands, flower stands and butchers.

But now I live in Oakland, and so a few weeks back I was stoked to hear that a new shop — hotly anticipated among Bay Area cool-clothes appreciators for months — had finally opened its doors on a similarly small-town-vibed stretch in San Francisco.

The shop is called Rising Star Laundry. Its owners are Nicole Solano and Brody Nowak, friends who met working at the now-defunct SF shop Unionmade. I caught wind of RSL back in January, when Nowak hit me up through a mutual buddy about carrying clothes from the elite garment-crafting Spyfriends of James Coward — a promising sign of great taste. RSL became James Coward’s sixth-ever stockist, carrying them alongside lines like Japan’s Yoko Sakamoto, Denmark’s Mfpen and Lyon’s Arpenteur.

I popped in on a recent Saturday, and could almost smell the fresh paint. They’d soft-opened just two days previous, their website was still a “coming soon” placeholder, and their Instagram was still empty. Their priority, they told me, is to focus on embedding themselves in their neighborhood, Cole Valley. “We just wanted to open our doors to the community, not even post about it online, and see how it went,” Nowak told me. “And we’ve been shocked at the turnout. The past few days, all these people have been coming in, saying, ‘I heard you were open.’ I’m like, How??”

Like Carroll Gardens, Cole Valley is “a very neighborhoody neighborhood,” as Solano put it. “Our space used to be an old toy store.” Nowak added: “We wanted something that wasn’t in a heavy clothing-retail district. We were looking for coffee shops, book stores, wine shops, hardware stores…” “We wanted to meet people where they naturally are,” Solano said.

Solano used to be e-commerce director for Unionmade. She told me that, when you’re managing a shop’s online presence, “there can be a hyper-fixation on the wrong metrics,” e.g., juicing your Instagram follower count at the expense of your local customer base. “Online, you’re trying to reach as many people as possible. But I think there’s something to creating relationships here, and creating a space that’s about touching and feeling the clothes. That creates more longevity than optimizing a product page. I’d rather take the money for a targeted ad on IG and use it to sponsor a Little League team — a place where you see the name in relation to real life.”

When you talk about cool shops trying to make it in cool neighborhoods, the subject of rent can’t be ignored. Chris Green declined to tell me what he pays at Ven, as did RSL’s owners, but Nowak did say, “We got a great deal. It’s substantially below market. And that really helped us get the brands we wanted.”

A reminder that greedy landlords are the enemies of small shops carrying fire clothes near you!

Rising Star Laundry is self-funded. So is Ven. Space, which Green funds entirely himself, alongside his wife, a Toteme VP. He told me he could see a day where he launches a webshop that only carries Ven’s in-house clothing line, “because you can’t get it anywhere else, so that might be worth the exposure and the SEO to pay for it. That might make sense.”

Nowak and Solano predict that, down the line, despite their best efforts, foot traffic alone probably won’t sustain Rising Star, at which point they’ll have to figure out a lean, workable e-comm strategy. “We’re probably not going to be able to get around it,” Solano said, “But if we could, I’d love that.”

III. “There are so many factors that are out of your control”

There are shops, however, that have gotten around it for years. A prominent one is Montreal’s beloved Les Étoffes, which opened in 2008, and where the brand list over the years has included Lemaire, Patrik Ervell, and Dana Lee. Les Étoffes has never had a webshop, and the other day I called the owner, Diana Taborsky, to ask how she’s made it work without one.

She told me she’d opened the shop with her now-ex-partner in the city’s Mile End neighborhood back when “it was a bit of a no-man’s land, a little derelict,” she said, securing a lease that locked in her base rent at every renewal. That cost stayed stable as the neighborhood got more bustling: “I’m surrounded by all these mom-and-pop shops now.”

Beyond manageable rent, Taborsky emphasized that, “when it comes to your product matrix, if you can offer exclusive things people can’t get anywhere else, that’s really important.” To that end, she’s picked up a lot of local jewelers, a lot of slept-on Korean lines, and dropped certain other better-known lines over the years, even though she loves them, to tighten the belt and avoid overlap with, among other competitors, her fellow Montrealers at Ssense.

“Their markdown strategy is really what I have a problem with — they make it tough,” she said. “When I go to a showroom and talk to a brand that Ssense carries, I ask what styles they’ve bought and try to avoid those. It’s an uncomfortable question, but a necessary one. Sometimes I buy a style and I forget to ask — I just loved it — and when I see they don’t carry it, and it sells through for me, I’m so stoked. That’s a win for me.”

Ssense HQ is a short drive from Les Étoffes, and over the years Taborsky said she’s seen the site’s buyers come in and do recon on under-the-radar lines she stocks. “That happens less now, because they’re pretty dialed in at this point,” she said. “The damage is kind of done on that front.”

Finally, she stressed the importance of “fostering relationships with my clients. That’s the No. 1 thing, that’s why I’m here. My clients return every season, God willing, they like the experience, they prefer coming into a store to shopping online.” She keeps certain customers in mind for certain pieces. “I text them — we have a client list and a waitlist for certain things. It’s about that one-on-one personalized stuff, shopping appointments, a little newsletter.”

Like Chris Green, Taborsky cited e-comm’s “crazy overhead” as a major sticking point when it comes to the prospect of selling clothes online, along with aggressive markdown schedules and marketing costs. She also brought up more arcane but no less meaningful question marks like exchange rates (the Canadian dollar is particularly low at the moment) and logistics: “Canada Post is on strike now, and all these stores with webshops are dependent on that service. There are just so many factors that are out of your control when you go the online route.”

And yet Taborsky told me she’s been forced into a crossroads. Coming out of Covid, her longtime landlord sold the building to a real estate group, “and they doubled my base rent.” As a result, she believes she’ll have to figure out some tentative path into e-comm before too long. “I’m such an offline person, I’d have to find a way that isn’t an affront to my sensibility,” she said. “I’m not gonna rush into it, and I can’t put all my eggs in that basket. But the potential to make more sales is there. I’d love just a little piece of that pie.”

IV. The Inspiring Conclusion: A virtuous cycle of real ones

My reporting wasn’t done until I tapped in with two legendary, e-comm-averse, clothes-selling Real Ones.

Back in October of 1980, Jeri Ospital opened San Francisco’s legendary MAC, a.k.a. Modern Appealing Clothing, with her son Ben and daughter Chris. Chris had worked as a buyer at Bloomingdales in NYC. Ben had worked as a buyer at Saks, a couple avenues over. “The three of us signed the lease on a 300-square-foot space in the Tenderloin,” Chris told me recently. Before long, MAC became known as a forward-thinking spot to find adventurous labels, many of whom MAC still stocks alongside younger lines like Casey Casey, Wright & Doyle, Julie Kegels, and Meryll Rogge. Jeri Ospital died two years ago, age 94, leaving her kids to run the shop.

From the start, MAC’s clientele drew heavily from the Bay Area’s arts crowd. It’s also long been a destination for simpatico visitors: Madonna popped in during the Like a Virgin tour; John Waters became a regular; it’s in any tourist guide worth its salt.

The shop, which currently occupies a high-ceilinged storefront in Hayes Valley, briefly flirted with e-commerce in the mid-2010s, joining Farfetch. But that wasn’t how they want to run the business. Chris said that shopping online is better for “general things. ‘I need a black pair of stretch pants.’ But for anything specific, for anything more personal to you,” she continued, “the in-person experience” is unparalleled.

“We never want to trade in disappointment,” Ben said. “And, you know, three black garments from Comme des Garçons all look the same in pictures. So people would receive their orders and tell us, ‘I didn’t realize it was this.’ So you end up with a return, and returns are very hard when you’re small.”

Like Taborsky from Les Étoffes, Ben described the ongoing goal at MAC as forming and then tending to “a community,” and not in the cooked contemporary marketing-speak sense: “When you look at these e-commerce sites, you say, ‘They just reduced everything to a floating image on a white background. There’s no context.’ We’re all context!” For instance, MAC hangs artwork by artists they know, who in turn call them up when they need things to wear to openings — as the painter Léonie Guyer did last month, before the reception for her solo show at the House of Seiko gallery in the Mission. Ben & Chris tell shoppers which Bay Area restaurants to eat at, and those restaurants direct diners to MAC in turn. “We’re all clarions for each other,” Ben said.

It’s a cool, throwback, funky, small-town-in-a-big-city vision of commerce — one enabled economically in MAC’s case, the siblings explained, by two major factors. The first is that “we have a very, very nice situation with our landlord, who’s a landlord, not a corporation,” Ben said. “We’ve had good leases and bad leases over the years, and at the end of the day you’ve got to be able to have rent you can afford while still doing what you want. From time to time, we get offers from developers asking, ‘Would you like to open a MAC here?’ But with the rent they quote us, we couldn’t be as interesting in what we buy.” Chris explained: “We’d have to sell something else. Easy gets. A simple black turtleneck under $200 — there’s tons of other places you can find that. We don’t want to sell that. We want to sell the Junya Watanabe dress shaped like an Isosceles triangle.”

Which leads to the second factor: “Client building,” Ben said. Their bread & butter lies in sustaining relationships with a local demimonde who A. trust their taste and B. have the money to splash out in the name of that trust, whether it’s on an isosceles-triangle Junya dress or an understated Dries suit. “We have great rapports with people going back years,” said Chris. “We know what they bought last season, so we can call them and say, ‘We just got in this skirt, come see it.’”

Ultimately — like Green at Ven. Space, Nowak & Solana at Rising Star Laundry, and Taborsky at Les Étoffes — the Ospitals are more interested in doing something unique and exciting to them and focusing on making that economically feasible, rather than trying to chase ever-greater profits and scale. For them, e-comm is a hindrance, rather than an aid, to that fundamental mission.

“I always tell people, We run a really fun non-profit,” Ben said.

Diana Taborsky put it this way: “I’m not trying to snort up the entire universe. I’m just trying to cater to my people.”

Peep our list of the world’s 35 slappiest shops, where Spyfriends have added a ton of gems in the comments.

Check out our comprehensive Home Goods Index.

Excellent reporting. Re: declining to tell people your rent (which in this case I'm sure is for a good reason re: their relationship with their landlords or something)-- reminds me of a fave maxim: tell anyone who asks what you get paid, what your rent is, etc.

The culture of silence around expenses in this society is legit a tool of capitalist and anti-union forces. 🤷🏻♀️

I was at Ven a couple of Saturdays ago for the first time and the place was buzzing. I didn't leave with anything but really wanted to find a way to support Chris + his team in some way.

On the way home, I wondered if more of these types of shops might opt out of ecomm and instead run a *Shop + Substack* strategy.

As a client, one of the key reasons to visit Ven is the team's curation and perspective. What's coming up, what's out, brands they love, colors they're buying, why they're excited about X new brand...

I would happily pay $5 a month to get that knowledge delivered and support Ven between big purchases.

For the shop, it's a predictable revenue stream. For the client, it means being a part of the community and maybe it comes with added benefits (events, sales, launches, etc). For Jonah and Erin, it could be a very fun consulting project :)