The wild inside you

Paying hallucinatory attention, the tricks paintings play on our eyes, chasing beauty in an art world suspicious of it & more with the great landscape painter John McAllister

Our interviews with Nathan Fielder, Brendan from Turnstile, Adam Sandler, Issy Wood, Andrew Kuo, MJ Lenderman, Kim Gordon, Steven Yeun, Maya Hawke, Bon Iver, André 3000, 100 gecs, Matty Matheson, Laraaji, Eckhaus Latta, Mike Mills, Tyler, The Creator, John C. Reilly, Rashida Jones, Camiel Fortgens, Father John Misty, Kate Berlant, Clairo, Conner O’Malley and more are here.

Mach 3+ city intel for traveling the entire planet is here.

Check out rugs, cushions, lamps, ceramics and more in our Home Goods Index.

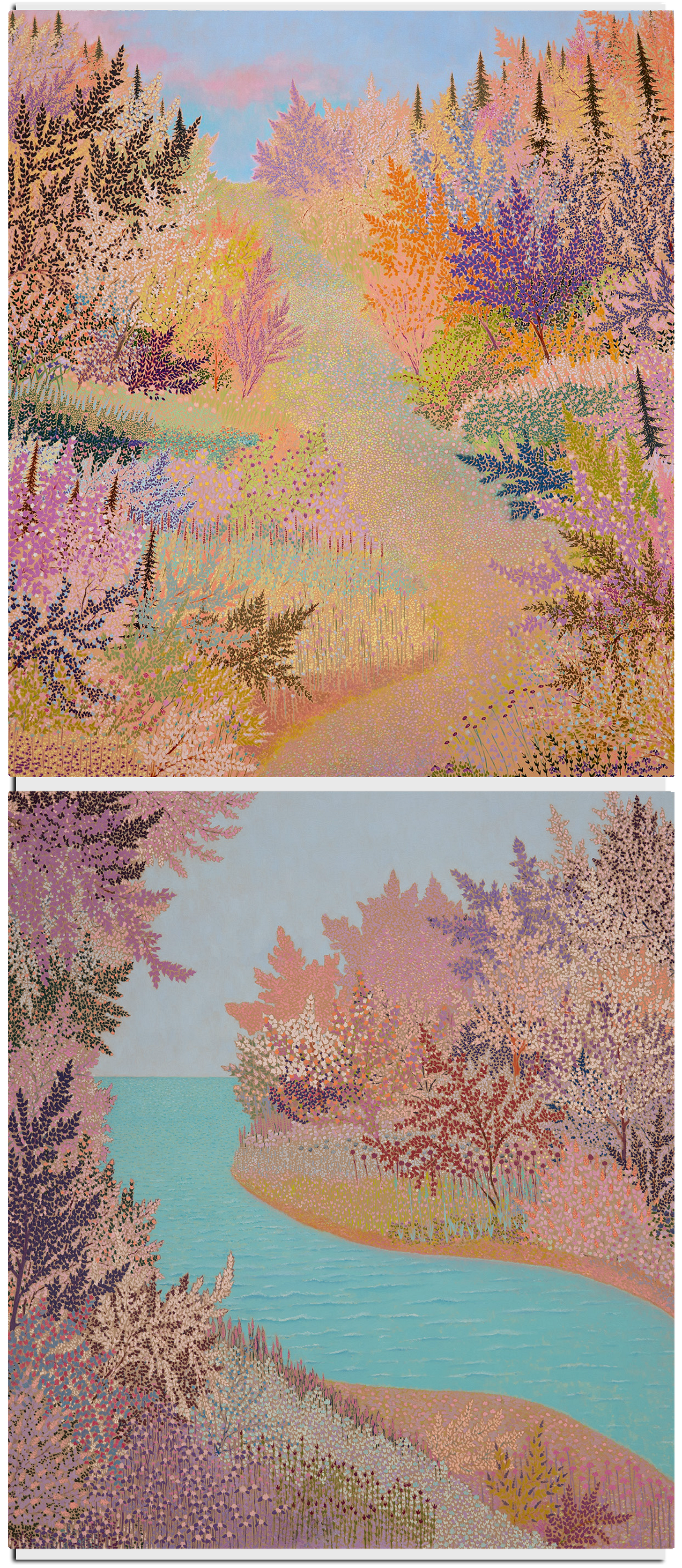

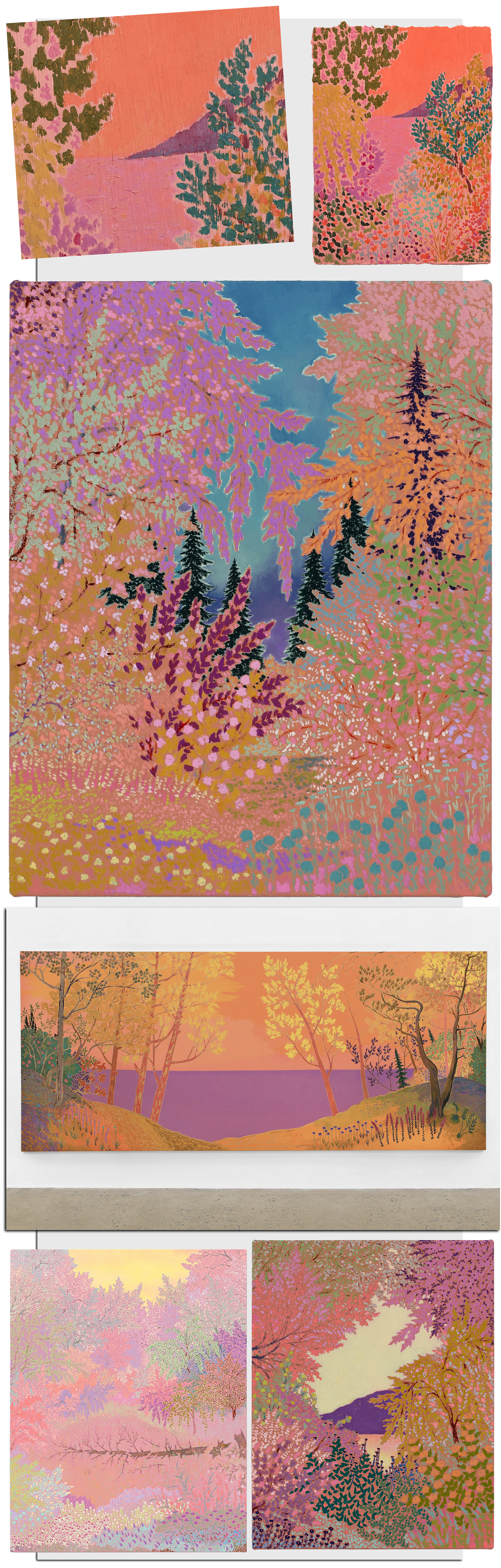

John McAllister is one of the great living landscape painters. His trippy scenes… his rich, pulsating sense of color… his gift for capturing the sensation of vibing out hard in beautiful wilderness and paying nature such close attention you feel like you’re hallucinating…?? It’s all profoundly up Blackbird Spyplane’s alley.

Erin and I discovered John’s work years ago through our friend James Fuentes, the NYC gallerist who’s represented him since 2008, when John was fresh out of art school. Before that, John worked for 6 years as a security guard at the Met, staring at paintings all day — its own kind of art school, too.

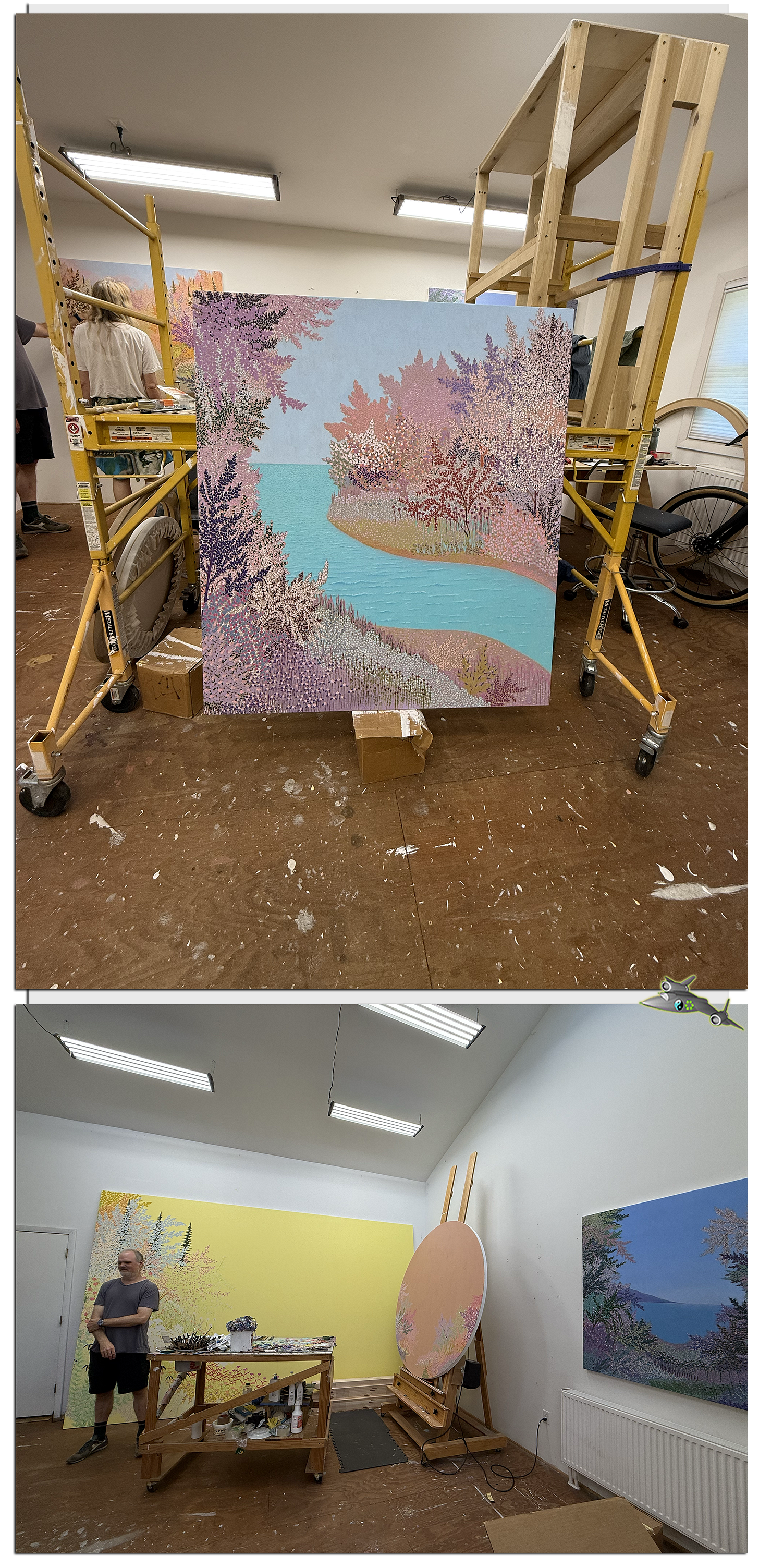

This Friday, September 5th, his latest show, sun sundry beguiles wild, opens at James Fuentes Gallery in Tribeca. James asked me to write the text for a little limited-run publication accompanying the show, and I eagerly agreed: John is not only nice with these brushes, but also chill, thoughtful, and extremely good at talking about how paintings can trick our eyes and invite our brains to link and build introspectively in the construction of that illusion.

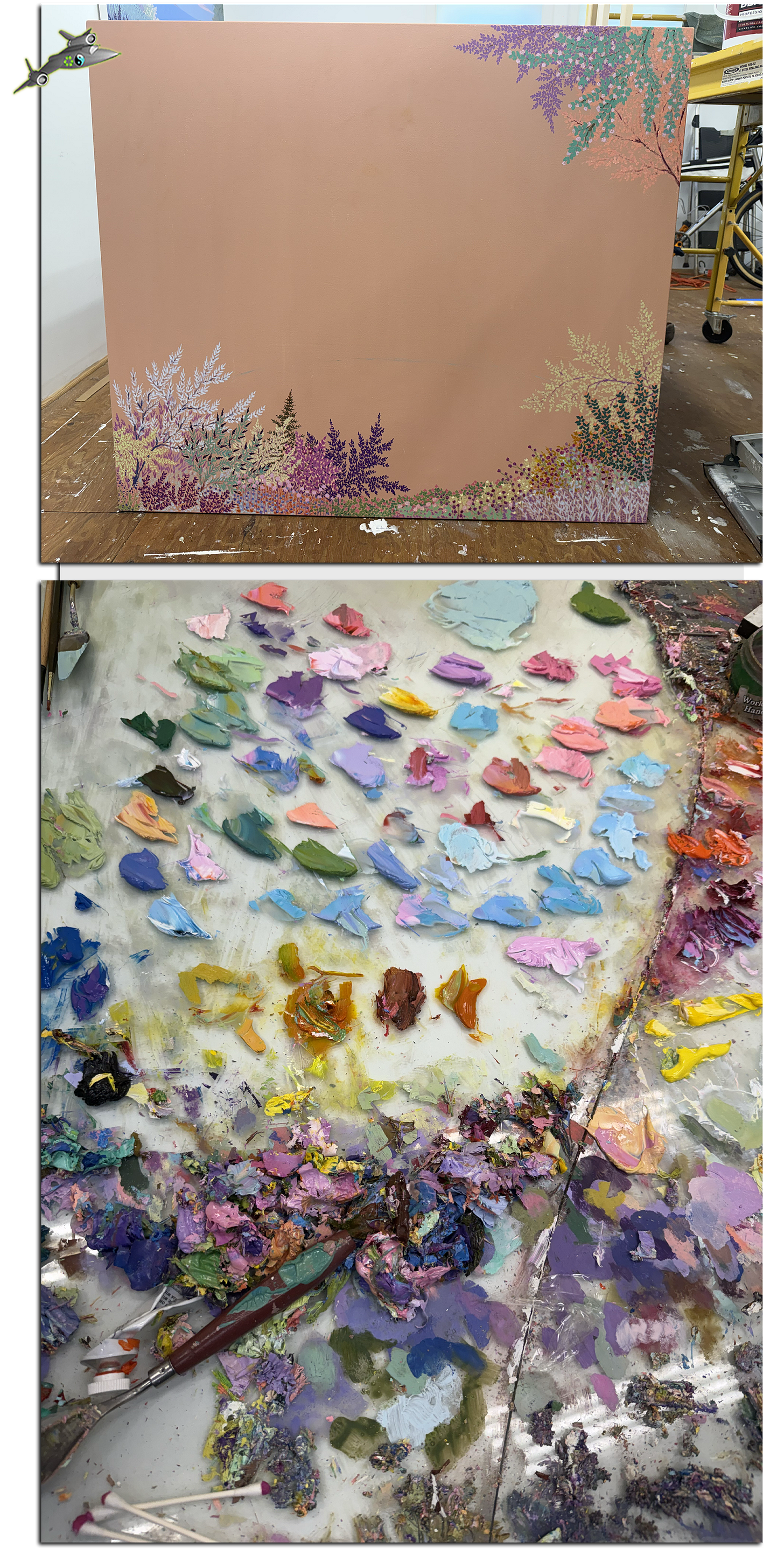

Today we’re kicking off a month-long Spyplane Fall Spectacular, full of Mach 3+ autumn cultural coverage we’ve got planned for you. For the many Spyfriends who can’t snag a physical copy of the Spyplane McAllister zine in person, we’re running my appreciation of John’s paintings here in the sletter, interspersed with process shots from his studio, taken as he worked on the new show.

If you are in NYC in the next month, do yourself a favor and see these stunners in person. While you’re there, pick up a copy of our McAllister zine before they’re gone.

John McAllister’s landscapes are a strange, vibrating, overwhelming kind of beautiful. They feel less like real depictions of places than hyperreal ones, which makes sense, because they bear no straightforward relationship to any actual place on earth that McAllister has ever been or seen. The paintings spring from his mind on the fly.

McAllister lives in western Massachusetts. He hikes in the Berkshires, not far from his home, and he rides a bike up in Vermont, but he has no interest in making pictures when he’s in nature. He doesn’t work en plein air, carrying paints and canvases with him. He doesn’t even snap photos to consult later on. His phone gets in the way of looking, so it stays in his pocket. When he’s back in his studio, “it’s important for me to divorce myself from nature entirely, to where I don’t hold myself up to it,” he tells me. There’s nothing on his studio walls — no tacked-up reference imagery to check his description of a flower against the genuine article. “It’s an entirely different form to be a mirror to nature than to reflect the effects of nature on a person,” he says. “And I’m much more interested in the affected mind, in the sensation of a landscape, than how it actually looks.”

It’s something like Phenomenological Landscape Painting. McAllister will find himself conjuring, say, a forest clearing. Its perspective lines, if you try to chart them, will not necessarily add up. “A flower, a leaf, they’re really forgiving in terms of scale and proportion, so you can do all kinds of bizarre things with perspective,” McAllister says. “It can make no sense and feel good at the same time, and that’s also part of what stops me in nature: When things don’t make sense. It’s that reaction of, ‘I understand this, but it’s off-kilter,’ and there’s a pleasure in that kind of awkwardness.”

McAllister’s colors don’t make strict literal sense, either, but they are full of pleasure, too. He might frame his clearing, impossibly, with blue leaves and creamsicle-orange flowers, throbbing under pink and yellow skies. He negotiates between Monet pastels and borderline-garish Miami Beach hues, rendering woodland scenes with tropical and almost chemical palettes. One of his gifts is that he never tips into grotesquerie or abject kitsch. “It’s about edging up to corniness — you get near Miami, but you stay in Provence,” he says. “I like artificial colors in a natural setting, because for me, it’s always about choosing the thing that extends itself beyond the ordinary. All this artificiality presents opulence, and then you can soften it all, so it’s soft and inviting and chaotic at the same time.

“I always think about how something corny can make you almost nauseous, how powerful that is,” he continues. “If you can go right up to the edge and not fall over, that’s a really potent thing to use.”

On one level, McAllister’s paintings are fantastical. But since he is chasing a sensation, there’s a trippy kind of verisimilitude at play all the same. I do a hike in the Oakland hills, a continent away from McAllister and the Berkshires, where a spur trail overlooks a canyon dense with chaparral, sage, poppies, eucalyptus, oaks, madrone, mustards, shiny bay leaves, shinier poison oaks, and little universes of lichen. Pops of purple, orange, red and yellow notwithstanding, the canyon is mostly greens and browns. And yet, even in that field of earth-tones, there is a pulsation of light and color, not to mention of smells, insect buzz, and birdsong. There is a quasi-hallucinatory effect if you look long enough at any density of plants, swaying in the breeze and the sunshine with bugs and birds around — and it’s this effect that McAllister somehow captures through color and form.

That capture begins at the level of brushwork. Whether he’s working on a canvas the size of a gallery wall or the size of a magazine cover, McAllister always uses the same small brushes to make the same loose marks. “Looking at a landscape in nature, standing at a distance, you don’t see the contours of every leaf,” he says. “You see a collection of color, a mass composed of a million little things. So I’m using precisely placed loose marks to simulate that. I like that it still remains a brushmark, at the same time that it’s also a description of something.”

In much the same way that the places McAllister paints do not exist, neither do the plants. “A botanist would lose their mind looking at any of these paintings,” he says. “I’m making them up. I look for shape and texture, and balance those off each other. There’s a new painting” — ablaze rapt chorus beaming, pictured in-progress above and completed below — “with this strip of reflection on the water that, in person, you almost need sunglasses to look at it. And as the plants get close to the water, they’re like these little soft explosions. I’ll be having that thought while I’m painting them, and I’ll find myself making an audible little sound while I do, without realizing it. I’m going for this phenomenological feel, and so I’ll look for shapes that either contrast or go along with what’s there. The color has to perform that way, too. It’s all performative: The leaves and the flowers are a structure to perform upon. They’re the allowance for these colors and shapes to be there.”

McAllister creates an illusionistic space, in other words, but he keeps the illusion explicit. The effect is a sustained kind of paradox in his paintings, and it contributes to their pleasant uncanniness: They feel simultaneously lush and flat. “Even if you see thousands of tiny marks, you can also always see that as a window,” he says.

This connects to something McAllister loves about Monet, whose work he first saw in person when he was right out of college, working as a security guard at the Met. “One of my favorite things about painting, and Monet, and postimpressionists in general, is this thing where you look at it and into it at the same time,” he says. “You’re always aware of the artifice of the thing, even as the artifice is susceptible to disappearing. It reveals that the painting is taking place inside your mind. You’re assembling it inside your brain, taking it in. My mark is always teasing that relationship of being both highly representative and overtly there on the surface.”

McAllister’s devotion to beauty can make him something of an odd man out in an art world frequently suspicious and dismissive of it. He got his MFA at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, where the faculty included Mike Kelley. “He was an unbelievably amazing artist, he was the reason most people were at that school,” McAllister says, “and if I’m honest, when I got there, I didn’t know who he was. When I applied, I wrote about Monet. I might have been the only person who ever did that at Art Center.”

McAllister loves Monet, Matisse, Bonnard, the Fauvists. I wonder if he has often felt like someone swimming against prevailing currents. “It’s where I find myself regardless, I don’t have a choice in the matter,” he tells me. “I’m not setting out to counter anything. I’m positive in what I’m making — not in the sense of a positive disposition, but in the sense that I view it as an addition, a continuance of art history.” When a painting catches his eye, “my interest is, I stick my nose in it, then step back. It’s still very traditional in that way.”

For his MFA show, in 2007, McAllister painted barns and other wood structures consumed by enormous, raging flames. With time, he began to paint wallpapered sitting rooms with little landscape paintings mounted within them. And before long, those landscapes took over the canvases, edging out the man-made structures and spaces entirely. “If there’s an overt, person-made structure in a picture, it tends to become the content of the thing. It can really dominate,” McAllister says. Without any of that, “you can get into the phenomenological aspects of things, and that can be the overriding aspect of the painting — how the color makes you feel, how getting lost in it can make you feel. For me, those bridges in Monet’s paintings destroy the paintings. They’re the most violent destruction. Because suddenly you’re thinking of geometry, these human-organized things.”

Of course, the man-made is, on a fundamental level, inescapable in the Anthropocene. McAllister is ambivalent about that, and his work embraces that ambivalence. “I like that cultivated plants pop up all over the place. All the forests in Massachusetts are basically new growth, because they were all cleared for sheep. I know that this meadow is here because we cut down these trees for cattle.” Pollution deranges the sky. Eerie wildfire light, too. “I’m always aware of how good I feel in nature, and how much we’ve messed it up,” he says.

I ask McAllister if he has ever seen Alex Garland’s Annihilation, a movie about a strange, swampy swath of Florida where the flora mutate at an accelerated rate, assuming enthrallingly hypertrophic forms and lurid colors — a woozy zone where the people who enter do not come back the same, if they come back at all. Not unrelatedly, I ask him if he ever eats magic mushrooms when he’s hiking, or when he’s painting.

His answer to both questions is, No. “But when I’m making these paintings, and listening to music, I’m often tuning myself, in order to have that kind of euphoria,” he says. “Sometimes what I’m looking for to finish a painting is this moment of euphoria and electricity. I want it to feel slightly disorienting, but beautiful. Which is what a mushroom trip is.”

Motifs recur from painting to painting. A meadow cradles the sky like a bowl of fruit. We glimpse a mountain rising from a lake through a tunnel of trees. As McAllister paints, he thinks back to those moments, out on the trail, “when I stopped, without thinking about it, to look. And I ask myself, ‘It’s all beautiful, so why did I stop there?’ And it’s usually because there’s all these prosceniums presented to you, like a theater, whether there’s an opening you gaze into, often there’s water, often it’s somewhere you can see further, like a valley. Basically, it’s a moment that is not ordinary, and it holds your gaze — and that initial impulse to look at the thing turns into introspection. I say to myself, ‘Well, this is what a painting should do.’”

sun sundry beguiles wild is up from Sep. 5 - Oct 5 at James Fuentes Galley, 52 White St, New York, NY, 10013

The B.L.I.S.S. List — a handy rundown of Beautiful Life-Improving Spyplane Staples, from natural deodorant to socks and underwear — is here.

Classified-Tier Spyfriends request, share and receive Mach 3+ recommendations in our SpyTalk Chat Room.

Beautiful. It just so happens I have Merleau-Ponty's "Cézanne's Doubt" on the nightstand, very much soaking in the same tub – "He wanted to put intelligence, ideas, sciences, perspective, and tradition back in touch with the world of nature which they were intended to comprehend. He wished, as he said, to confront the sciences with the nature "from which they came"" – yet arriving to a very different end result in terms of overall vibe. Cool 🫡

So rich, this. Thank you. I did not know McAllister's work at all - but I've actually lived in Northampton (until very recently), overlapping with him, and for a long time in Oakland, and it is so easy to see the way hikes in both places can invite efforts to re-imagine natural scenes. For some reason the colors he chooses for "Western MA" scenes make sense to me - as if their scenic splendor called out for other places, other tones. I also love his discussion of "tuning" himself. Relatable!